ⓘ Let’s Set the Record Straight First

Nursing homes cannot place a lien on or “take” your home. This is one of the most common misconceptions families carry into estate planning conversations — and it’s understandable, since nursing homes are where the care occurs and where the bills arrive. But legally, nursing homes are healthcare providers. They do not have the authority to pursue your property.

The real threat comes from the state government through Medicaid’s estate recovery program. After a Medicaid recipient passes away, the state — not the nursing home — may seek reimbursement from the deceased’s estate for care costs it paid. Families often direct frustration at the nursing home when they receive financial notices, but those actions are entirely driven by government law and government agencies.

It’s also worth knowing that nursing homes frequently lose money on Medicaid patients. Medicaid reimbursement rates are often below the actual cost of providing care, and facilities must make up the difference through other revenue. The financial pressure families experience reflects government-set program rules — not nursing home billing decisions. Planning early with a qualified elder-law attorney is the way to protect your home from the government’s recovery process.

To get clear, reliable answers at your attorney meeting, come prepared with your recorded deed or a recent title report, plus a one-page timeline outlining ownership changes, residency periods, transfers, and care events. Request a dated, written Medicaid analysis that reviews any transfers within the past five years (the “look-back period”), calculates any penalties, and explains in plain English what happens to the home during eligibility and later under estate recovery.

Families who successfully protect their homes are those who plan early, meticulously document everything, and avoid changing title until their strategy is fully clear and confirmed in writing. Don’t rely on hope — take proactive steps to ensure your home’s protection.

Three Hard Truths About Protecting Your Home

Families often make what seems like an obvious move—adding a child to the deed, signing a quick quitclaim, shuffling money after a hospitalization—only to get blindsided when Medicaid reviews the past five years. If your goal is keeping nursing home costs from forcing a sale of your home, you need to anchor your decisions in three fundamental realities.

Your home faces two separate threats from the state government’s Medicaid program — and you need a plan for both. Nursing homes provide care; it is the state government that poses the legal threat to your home. The first threat is eligibility: whether the home counts as exempt or countable when you apply for Medicaid. The second is estate recovery: whether the state can seek repayment after your death from assets in your estate. A home might appear “safe” for eligibility purposes yet still be exposed later if it passes through the wrong kind of estate or if your plan was never fully executed.

Timing isn’t a minor detail — it’s the heart of your strategy. Medicaid’s five-year look-back is a thorough financial review conducted by the government. Any transfer made within 60 months of applying for long-term care Medicaid can trigger a penalty period during which Medicaid simply won’t pay for nursing home care. A trust, deed, annuity, or promissory note can absolutely work—but only when it fits your timeline and gets executed correctly.

The winning move is usually the boring one: get the facts into a file and demand a written conclusion. Your recorded deed, chain of title, and date-stamped timeline let a skilled elder-law attorney give you a defensible plan—whether that means spouse protection, a caregiver-child transfer, a Medicaid Asset Protection Trust (MAPT), or a lawful spend-down. Skip the verbal reassurance. Get something you can follow and prove later.

Documents That Change Everything

Scattered paperwork is one of the most common reasons families lose time—and sometimes lose planning opportunities entirely. Medicaid planning isn’t just about what happened; it’s about when it happened, how it was documented, and what legal ownership looks like today.

Expert Insight

One thing I’ve noticed working with families in New York and New Jersey is that the fear of losing a home to nursing home costs is both deeply personal and full of misconceptions. People are often surprised to learn just how easy it is to trip up on technicalities—what feels like a small, harmless change in ownership or a well-intentioned gift can have long-lasting financial consequences. The rules around Medicaid eligibility and estate recovery are complicated and the timing of your decisions is everything.

It is also important to understand that the financial concern is with government Medicaid policy, not with the nursing home itself. Nursing homes are required by law to accept the Medicaid reimbursement rate the state sets—and that rate often does not cover the full cost of care. Families sometimes direct frustration at nursing home administrators when they receive financial paperwork, but the rules, the recovery process, and the share-of-cost calculations are all driven by the state and federal government. At NY Wills & Estates, we’re constantly helping families understand this distinction and navigate the real source of risk. Clarity comes from gathering the right documents early and asking the right questions before making moves. The only truly safe plan is the one that’s informed, specific, and in writing.

·

NY Wills & Estates

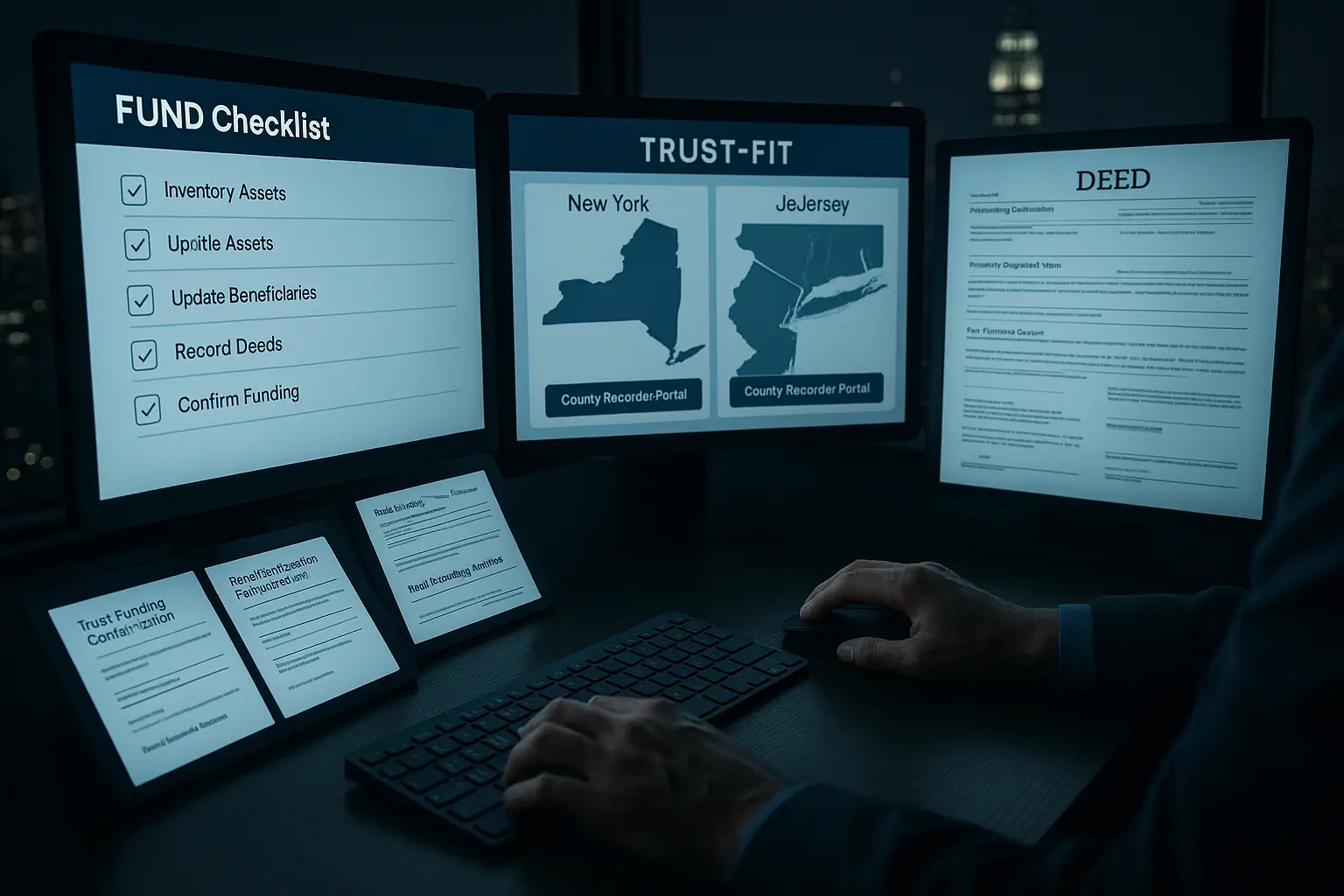

When you bring the right documents to your first meeting, your attorney can jump from general education to case-specific analysis immediately. That speed matters even more in the New York/New Jersey metro area, where families often face cross-state complications—moves, second properties, different county practices—that need to be spotted early.

| What to Bring | Why It Matters |

|---|---|

| Recorded deed | Shows legally effective ownership and the recorded date—often the anchor point for analyzing transfers, exemptions, and look-back calculations. |

| Recent title report | Confirms chain of title and reveals liens or past transfers when deeds are missing or unclear. |

| County clerk property search | A practical alternative that quickly reveals current title and identifies recorded documents your attorney should pull. |

| One-page timeline | Key dates in one place—moves, hospitalizations, caregiving periods, transfers. Helps your attorney spot problems and potential exemptions right away. |

Here’s a real-world example: Say a parent recently moved from home into a nursing facility and the family isn’t sure whether to sell, transfer, or leave things alone. The recorded deed plus a timeline often let an attorney identify the biggest risk points in that very first meeting.

When you schedule your consultation, ask whether the attorney can provide a dated, written conclusion—even if preliminary—identifying potential look-back issues, likely eligibility or penalty exposure, and what documents are still needed. You’re not asking for promises. You’re asking for a process that produces something actionable.

Why Timing Makes or Breaks Every Plan

Most home-protection strategies live or die on timing. Medicaid reviews transfers made during the five-year look-back period measured from your application date. A well-drafted trust or deed strategy can be powerful, but that same step taken at the wrong time can trigger a penalty period when Medicaid simply won’t pay.

A strong plan balances four factors: control (who keeps decision-making power), permanence (how hard it is to undo), tax impact (especially future capital gains), and timing (look-back exposure).

| Factor | 1 (Low) | 3 (Medium) | 5 (High) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | You give up decision-making power | You keep some rights but need cooperation | You keep full control |

| Permanence | Easy to reverse | Hard to reverse without cost and consent | Effectively irreversible |

| Tax Impact | Higher risk of losing step-up in basis | Mixed or case-specific | More likely to preserve favorable treatment |

| Timing Safety | Inside look-back, penalty likely | Borderline, needs precise calculation | Outside look-back, penalty unlikely |

Families naturally prefer options that feel best for control or taxes. But timing can override those preferences entirely. When two strategies are close, the one that fits cleanly into a safer timing window typically produces fewer surprises and fewer emergency fixes down the road.

For families in New York or New Jersey, it also matters whether your advisor truly focuses on Medicaid planning as a primary practice area. Small mistakes—dates, deed language, funding steps, beneficiary designations—can create outsized consequences.

The most common timing mistakes we see include transferring property or funding a trust only after a health crisis begins, without understanding the penalty implications; assuming an exemption (like caregiver child) will apply without gathering proof early enough; and completing gifts within five years of a Medicaid application and being caught off guard by the penalty calculation. If nursing home care looks likely within 2–3 years, you and your attorney must evaluate whether a transfer would clear the look-back by application time. If not, a different tool—or a lawful spend-down—may be the safer path.

Essential Medicaid Terms You Need to Understand

Medicaid planning comes with its own vocabulary, but the core concepts are straightforward once you see how they affect your home.

The Five-Year Look-Back

When you apply for long-term-care Medicaid, the state agency combs through financial activity and property transfers from the prior 60 months before your application date. If they find a gift or below-market transfer, they can impose a penalty period—a stretch when you’re otherwise eligible but Medicaid still won’t pay. That’s exactly why your attorney cares about exact dates: signing vs. recording, funding vs. drafting, deposit dates, closing dates. Penalty calculations are built on verifiable events, not rough estimates.

Medicaid Share of Cost: A Government Rule, Not a Nursing Home Rule

One of the most misunderstood aspects of Medicaid-funded nursing home care is the share of cost. When Medicaid pays for long-term care, it does not typically cover 100% of a resident’s monthly cost. Instead, the state calculates how much the resident must contribute each month based on their income. In most cases, the resident’s share of cost equals their total monthly income minus a small personal needs allowance — often just $35 to $50 per month, depending on the state.

For example, if a resident receives $2,000 per month in Social Security and pension income, Medicaid may require that approximately $1,965 of that go toward the cost of care each month, with Medicaid making up the remainder. Families are often surprised and frustrated when they see these calculations—and they often assume the nursing home is imposing these rules. The nursing home is not. Share of cost is entirely a government program rule set by the state and federal Medicaid agencies. The nursing home simply receives whatever amount the government sends after deducting the resident’s share. Because Medicaid reimbursement rates are often below the actual cost of providing care, many nursing homes actually operate at a loss on Medicaid residents and make up the difference through private-pay or Medicare patients.

Exempt vs. Countable Assets

“Exempt” typically means the home isn’t counted for eligibility under certain circumstances—most commonly when a spouse lives there and home equity remains below applicable state limits. “Countable” means your home equity can affect whether you qualify or force unexpected planning decisions. For most families, the practical questions boil down to: Is the home protected now? And will it be protected later from estate recovery? Those aren’t always the same answer.

Estate Recovery: The Government Threat That Comes After Death

Estate recovery is the state government’s process for seeking repayment after a Medicaid recipient passes away. To be clear: this is not a nursing home action. It is a government legal process under federal law (42 U.S.C. § 1396p) that requires states to attempt to recover Medicaid costs from the estates of deceased recipients. Even when the home was exempt during the person’s lifetime, it can become the primary target of state recovery if it goes through probate without protection.

Worth Knowing

How “estate” is defined for recovery purposes varies between New York and New Jersey. New York typically limits recovery to assets passing through probate, whereas New Jersey may pursue recovery more broadly in certain situations. Because these rules are technical and subject to change, it is important to confirm the current scope with a New York/New Jersey elder-law attorney. Ask the attorney to cite the specific authority they rely on and when it was last reviewed.

The recovery claim comes from the state’s Medicaid agency — not from the nursing home. Nursing homes have no role in the estate recovery process.

Here’s an example: A mother owns a home, enters a nursing home, and later dies. Even if the home wasn’t countable for eligibility, estate recovery rules determine whether the state government can seek repayment from the home—unless a spouse exemption, protected transfer, or other strategy applies. This is where coordination between Medicaid planning and estate administration makes the difference between a clean transition and a costly surprise.

| Term | What It Means for Your Home |

|---|---|

| Five-year look-back | The state reviews transfers from the prior 60 months. Gifts or below-market transfers typically trigger a penalty period. |

| Share of cost | A government-set rule requiring the Medicaid recipient to contribute most of their income toward care costs each month. Not a nursing home fee — a Medicaid program rule. The nursing home receives what the government pays after this deduction. |

| Exempt vs. countable | The home is often exempt when a spouse or qualifying relative lives there and equity stays below state limits. Otherwise, it may be countable or vulnerable to estate recovery. |

| Estate recovery | After a Medicaid recipient dies, the state government may seek repayment from the estate. The home is frequently the largest target unless proper planning applies. This is a government action, not a nursing home action. |

The DEED Framework for Home Protection

To keep your planning focused, use DEED—a four-step checklist built around the very document at the center of every home-protection decision. Every step is designed to replace vague reassurance with dated proof and written conclusions you can actually rely on. If your plan can’t pass all four steps, it isn’t ready to execute.

D is for Determine which state’s rules govern. Confirm which state’s Medicaid rules apply to your situation and whether you have cross-state complications. Ask your attorney to identify the controlling sources (statutes, regulations, agency guidance) and when they were last updated. Much of the confusion families encounter comes from mixing rules across states or relying on outdated information. Your attorney should tell you, in writing, which state’s rules apply to your application and which authorities they’re relying on.

E is for Exact dates are everything. Pull the recorded deed and confirm precise dates—signing, recording, funding. Penalty analysis must anchor to the specific event the state agency will actually use: the recording date, the closing date, the trust funding date. “About four years ago” is not a planning date. The difference of even a few weeks can move a transfer inside or outside the five-year look-back window, changing the entire calculus of your strategy.

E is for Exemptions require proof. Identify which exemptions may apply—surviving spouse, caregiver child, disabled child, sibling with equity—and what documented evidence Medicaid will actually accept. If that proof doesn’t exist yet, treat the exemption as unproven until it does. Your one-page timeline (who lived in the home, who provided care, when institutionalization began) is the foundation. Assuming an exemption will hold without organized records is one of the most costly mistakes families make.

D is for Deploy the right tool. Once the first three steps are grounded in documented facts, choose the right instrument: deed strategy, trust, annuity, promissory note, or lawful spend-down. The correct choice depends on your timing window, how much control you need to retain, liquidity requirements, and tax consequences for heirs. A plan that protects the home from Medicaid but creates a capital gains problem, a family-control conflict, or a cash-flow crisis is not a complete win—it’s a different problem.

Think you qualify for the caregiver child exemption? Work through all four DEED steps before assuming it will hold. Agencies typically want residency proof, medical records, and credible documentation that caregiving actually delayed nursing home placement. The exemption is the conclusion, not the starting point.

A Quick Self-Assessment Before Your Consultation

Use a simple 3-factor score to decide what deserves serious attention when you meet with counsel. Rate each potential strategy as High, Medium, or Low on control (can you still sell, refinance, or move without permission?), timing safety (is the transfer clearly outside the five-year look-back?), and tax risk (will heirs preserve a step-up in basis, or face a capital-gains problem?).

When a spouse lives in the home, many families prioritize strategies that protect the spouse’s ability to stay and maintain access to cash for living expenses. Often the best plan focuses on confirming the home’s exempt status during the spouse’s lifetime, coordinating income and resources for the community spouse, and addressing estate recovery risk—without forcing an unnecessary, penalty-triggering transfer.

When there’s no spouse at home, timing becomes even more decisive. With enough lead time, a MAPT or properly structured deed strategy may be worth exploring. But if you’re already inside the look-back, crisis planning tools or a lawful spend-down may be safer than a late transfer that creates an uncoverable penalty.

Certain red flags should pause any action: any transfer involving the home in the last five years (even “just adding a child”); nobody can produce the recorded deed or confirm the exact date of the last ownership change; you’re banking on an exemption without complete proof; or someone said “it should be fine,” but nobody provided a written penalty calculation tied to actual dates. If any of these apply, get a written analysis before changing title or applying.

Comparing Your Strategy Options

No strategy is best in the abstract. The right answer depends on how soon care is needed, your family dynamics, and whether you can realistically give up control. Here’s how the main options compare.

| Strategy | Control | Timing | Tax Considerations | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life estate deed | Medium | Remainder transfer typically needs 5+ years to avoid state penalty | Often preserves step-up in basis | Limits refinancing; can create family conflict |

| MAPT | Lower | Most effective when funded 5+ years ahead | Often designed to preserve step-up; drafting matters significantly | Drafting and funding mistakes can undermine protection. Not DIY. |

| Outright transfer to child | Low | State penalty if within 5 years (unless exemption applies) | Child typically receives carryover basis (often worse for capital gains) | Exposes home to child’s creditors or a child’s divorce |

| Medicaid-compliant annuity | Income retained; principal converted | Crisis planning tool when properly structured | Case-specific | Highly technical; incorrect terms can cause denial |

| Medicaid-compliant promissory note | Income retained; principal converted | Sometimes used in crisis planning | Case-specific | Must meet strict rules or treated as gift |

| Do nothing / lawful spend-down | Full control | No transfer penalty risk | No special planning; can still plan tax-smart spending | Often appropriate when inside look-back or facts are uncertain |

Situations requiring immediate written analysis include any home transfer (even partial) in the last five years, adding a child to the deed without documented Medicaid and tax review, relying on a caregiver or sibling exemption without organized proof, and having no written penalty estimate tied to specific dates.

How Each Strategy Affects Your Family

Life Estate: Stay in Your Home, But With Trade-Offs

With a life estate deed, you keep the right to live in the home for life, and the property passes outside probate. Done early enough, a life estate can support Medicaid planning goals because the remainder interest transfer can clear the look-back period. The downside? You generally can’t sell or refinance without cooperation from the remainder owners. This can spark conflict if circumstances change and complicate decisions when the home needs to be sold to fund care.

For example, Mrs. Jackson records a life estate deed in 2018 and applies for Medicaid in 2024. Because the remainder interest transfer falls outside the five-year window, she avoids a transfer penalty—assuming no other disqualifying transfers and proper execution.

MAPT: Protecting Assets With Structure

When properly drafted and funded, a Medicaid Asset Protection Trust removes the home from your name while preserving a structured plan for beneficiaries. Many are designed to preserve favorable tax treatment at death (including step-up in basis), though the specific design matters greatly. The drawback is that a MAPT requires early planning—typically at least five years before needing Medicaid. You’re giving up direct ownership, and errors in funding or title work can undermine the protection.

Consider the Petersons, who transfer their home into a properly drafted trust in 2019. If Medicaid is needed in 2025, the transfer is outside the look-back, positioning the home for both Medicaid and estate planning goals.

Outright Transfer: Simple on Paper, Risky in Practice

An outright transfer to a child is straightforward to execute, but that’s where the advantages end. It often creates a Medicaid penalty if made within five years (unless a specific exemption applies). It may trigger tax headaches—children typically receive carryover basis instead of a step-up, which can mean larger capital gains taxes when they sell. It exposes the house to the child’s creditors, lawsuits, and divorce proceedings. And it can ignite sibling disputes if expectations aren’t documented.

Mr. Liu deeds his home to his daughter in 2022 and applies for Medicaid in 2024. Unless an exemption applies, he’s likely facing a penalty period with fewer options than if he’d planned earlier.

Annuities and Promissory Notes: Technical Crisis Tools

In certain married-couple scenarios, an annuity can convert countable assets into an income stream that helps the spouse needing care qualify while the community spouse remains financially stable. Properly structured promissory notes may work in narrower, case-specific crisis situations. The rules are strict. Annuities must typically be irrevocable, non-assignable, actuarially sound, with fixed payments and proper beneficiary designations. Promissory notes must meet specific compliance requirements. Done incorrectly, either can trigger denial or penalties.

Spend-Down: Sometimes the Safest Path

Doing nothing—or doing a lawful spend-down—carries no transfer penalty risk and offers complete flexibility. Assets can be spent lawfully in ways that benefit you: paying debts, making certain home repairs, pre-need funeral planning, and other allowed expenses. The downside is that assets may be reduced to Medicaid limits without preserving wealth for heirs. If estate recovery risk isn’t addressed, the home may still be exposed later depending on title and state rules.

What Proof Do You Need for Exemptions?

Exemptions don’t apply automatically—they require proof. Exemptions work when the facts fit the rule and you can back up the required elements with credible records.

Surviving Spouse Protection

When one spouse needs nursing home care and the other stays in the home (the “community spouse”), the home is commonly treated as protected for eligibility purposes while that spouse lives there. What families often overlook is the second question: what happens after the Medicaid recipient dies and the state pursues estate recovery? Title, probate exposure, and state recovery rules determine whether the home stays protected. That’s why spouse-protection planning typically has two parts: protect the spouse’s ability to remain safely housed now, and coordinate ownership and estate planning so the home isn’t accidentally exposed to government recovery later.

Caregiver-Child Exemption

The caregiver-child exemption is powerful—and frequently misunderstood. The core idea: a child who lived in the home and provided care that delayed institutionalization may qualify for a protected transfer. In practice, the deciding factor is proof. Agencies typically want consistent documentation showing residency, care provided, and medical necessity.

Sibling and Disabled-Child Exceptions

These exceptions are narrower than many people assume. Sibling protections typically require specific ownership and residency facts. Disabled-child planning often demands careful coordination to protect the child’s own government benefits. If your situation might fit one of these categories, treat it like a claim you must support with a well-organized file—not a label to assert later without documentation.

| Exemption | Proof Commonly Needed | Federal Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Surviving spouse | Marriage certificate, residency proof (IDs, tax filings, utilities) | 42 U.S.C. § 1396p(b)(2)(A) |

| Caregiver child | 2+ years residency proof plus evidence caregiving delayed institutionalization (medical records, care documentation, affidavits) | 42 U.S.C. § 1396p(c)(2)(A)(iv) |

| Sibling with equity | Proof of co-ownership and at least 1 year residency before institutionalization | 42 U.S.C. § 1396p(c)(2)(A)(v) |

| Disabled child | Disability proof (often SSA documentation) and planning documents | 42 U.S.C. § 1396p(c)(2)(B)(iii) |

New York vs. New Jersey: Key Differences

| New York | New Jersey | |

|---|---|---|

| Look-back period | 60 months | 60 months |

| Home equity limit | Varies by year; confirm current limit with your attorney | Varies by year; confirm current limit with your attorney |

| Estate recovery scope | Generally focused on probate assets (state government action) | May be broader in certain circumstances (state government action) |

| Family exemptions | Caregiver child, sibling with equity, disabled child, spouse protections | Similar federal baseline; documentation expectations can be strict |

If you moved recently or own property in both states, build the timeline first, then match each event to the state rules that apply. Similar-sounding exemptions can play out quite differently in practice.

What to Bring to Your Attorney Meeting

Organize your documents systematically: arrange by date, and make it easy to verify what each document proves.

Deed and title records should include all recorded deeds (including life estate, corrective, or trust-related deeds), a recent title report (or county clerk property search showing current title), mortgage and lien documents plus payoff statements if relevant, and property tax bills and homeowners insurance for occupancy continuity.

Trust and estate papers include trust documents (revocable trusts, MAPTs, amendments, schedules), proof of trust funding (deeds into trust, assignment documents, account retitling), and estate documents (will, power of attorney, health care proxy, advance directives).

Financial statements means bank and financial statements (at least the last 12 months; 60 months may be needed for Medicaid applications), annuity contracts showing effective date and beneficiaries, and retirement and investment statements as requested.

Transfer documentation covers closing statements and settlement papers, cancelled checks, wire confirmations, receipts for major transactions, and gift documentation including dates and amounts.

Caregiving and residency proof includes residency proof (IDs, utility bills, voter registration, tax returns, leases), medical records supporting care needs and functional decline, and caregiving logs and sworn affidavits (dated, specific, consistent).

Ten Questions to Ask Your Attorney

A helpful consultation should end with more than a general sense of direction. You want written clarity you can act on.

- Is the home exempt or countable in my situation, and why? Ask for the specific rule being applied and whether that changes after death due to state estate recovery.

- Are there transfers inside the look-back? If yes, what facts are needed to calculate the penalty?

- Can you provide a dated, written penalty calculation tied to my exact transfer and recording dates?

- Which exemptions might apply (spouse, caregiver child, sibling, disabled child), and what proof will the agency typically accept in NY or NJ?

- What are the tax consequences of each option (capital gains, step-up in basis, gift reporting)?

- If recommending annuities, promissory notes, or trusts, what rules must the documents satisfy to be Medicaid-compliant in NY or NJ?

- Which statute, regulation, or agency guidance are you relying on, and when was it last updated?

- Can you give me a one-page scenario comparison? “If we do nothing” vs. “If we transfer” vs. “If we use a trust”—showing eligibility, penalty risk, and estate recovery exposure.

- Do you have any conflicts of interest—for example, relationships with facilities, insurance products, or financial advisors that could affect your recommendations?

- What’s the timeline and cost to deliver the written analysis and execute the chosen strategy?

What to Expect From a Quality Elder Law Firm

A reputable firm has a process that feels organized and evidence-driven, not improvised. Look for structured onboarding—a document request before the consultation plus a clear method for identifying key dates and potential look-back issues. Expect clear deliverables—a written summary of what was reviewed, what’s still missing, and recommended next steps. Insist on transparent fees—a clear engagement agreement explaining whether work is flat-fee, phased, or hourly. Confirm coordination capability—willingness to collaborate with your CPA or financial advisor.

For many New York and New Jersey families, the simplest way to cut through the overwhelm is working with an estate planning firm that does this work every day, in both states, with a clear process. NY Wills & Estates focuses exclusively on estate planning (wills, trusts, Medicaid planning, and estate tax strategies) and is licensed in both New York and New Jersey, with offices in Manhattan (450 7th Avenue) and Hackensack (15 Warren Street).

How to Use This Resource Safely

This article is educational and designed to help you prepare for a consultation with a licensed elder law or estate attorney in New York or New Jersey. Medicaid eligibility and estate recovery are state-specific and fact-specific, and agency practices vary. Rules can also change over time. This content is not legal advice and should not substitute for advice tailored to your situation.

Your Action Plan Starts Today

Day 1: Find the recorded deed (check your files, or request one from your county clerk’s office or online property records) and start a one-page timeline of transfers, occupancy, and care.

Within 1 week: Email organized documents and your timeline to an experienced elder-law and Medicaid attorney. Confirm whether they can provide a dated, written penalty calculation (if transfers exist) as part of the first-phase analysis.

Within 2–4 weeks: Review options side by side. Don’t transfer the home until you understand Medicaid and tax consequences in writing—including whether the home is exempt or countable and what estate recovery risk remains.

Ongoing: Keep a paper binder and digital folder updated with new residency and caregiving proof and major financial changes so future applications or agency follow-ups don’t become emergencies.

Frequently Asked Questions

-

Can a nursing home take my house in New York or New Jersey?

No. Nursing homes cannot place a lien on or take your home — this is one of the most common misconceptions in elder care. The legal threat to your home comes from the state government through Medicaid’s estate recovery program. Nursing homes are healthcare providers and have no role in that recovery process. If you’ve received paperwork or notices that feel threatening, they originate from a government agency, not from the nursing home.

-

What is Medicaid share of cost and why does so much of my income go to the nursing home?

Medicaid share of cost is a government-set rule — not a nursing home fee. When Medicaid pays for long-term care, the state calculates how much of the resident’s monthly income must be contributed toward care costs, typically leaving only a small personal needs allowance of around $35–$50 per month. The state pays the remainder to the nursing home. Families sometimes direct frustration at nursing home administrators when they see how little of a loved one’s income they retain, but this calculation is entirely driven by government Medicaid policy. Notably, Medicaid reimbursement rates are often below actual care costs, meaning many nursing homes operate at a loss on Medicaid residents.

-

Does adding my child to the deed trigger a Medicaid look-back penalty in New Jersey?

Usually, yes. Adding a child as an owner is typically treated as a transfer of value (a gift of part of the home) and can trigger a state penalty if it occurred within the five-year look-back — unless a specific exemption applies. Bring the recorded deed and any transfer documents to a New Jersey elder-law attorney for a fact-specific written penalty analysis.

-

Will Medicaid claim my New Jersey home through estate recovery if my spouse still lives there?

Having a spouse in the home provides significant protection during your lifetime for eligibility purposes. What happens after death, though, depends on state estate recovery rules, how title is held, and what planning steps were taken. This is a state government action — not something the nursing home initiates. Bring proof of spouse residency and ask for a written legal opinion based on your ownership and family situation.

-

Can a New York MAPT prevent Medicaid estate recovery for my home?

It can — when properly drafted and funded, meaning the home is retitled into the trust and the plan is implemented early enough to clear look-back rules. Trust design matters and details are critical. Ask your attorney for a written scenario comparison showing outcomes with and without the trust.

-

Is a four-year-old deed transfer protected from a Medicaid look-back penalty in New Jersey?

Not automatically. A transfer within five years still falls inside the look-back and commonly triggers a state penalty unless an exemption applies. Your attorney needs the exact recorded date and documents to evaluate exposure and provide a written penalty calculation.

-

What proof is needed to qualify for the caregiver-child exemption?

Typically: medical records supporting care needs, proof the child lived in the home for the required period (usually 2+ years), and credible evidence that care actually delayed nursing home placement. Care logs and affidavits help, but medical documentation is often the linchpin. Requirements can be strict — gather more documentation than you think you’ll need.

-

Who handles Medicaid estate recovery claims after a loved one passes away?

The state Medicaid agency initiates estate recovery — not the nursing home. The claim is addressed through the estate administration process, handled by the executor or administrator, often with legal counsel. Deadlines and required responses can be strict — speak with an attorney promptly after death.

Final thought: The fastest way to protect a home is to replace stories and guesses with dates, documents, and clear legal analysis. And the first step is understanding who the real actor is: not the nursing home, but the state government’s Medicaid program. Build the file, confirm the state rules that apply, and insist on written clarity before you transfer anything.

Schedule Your Consultation

Call NY Wills & Estates at 516-518-8586 to take the next step in protecting your family’s future. In a consultation, you can discuss your specific needs and goals with an attorney who focuses exclusively on estate planning and Medicaid-related planning. You’ll get clear answers about which documents and strategies fit your timeline — whether that’s early planning (like properly structured trusts and deed strategies) or crisis planning (like lawful spend-down and technical Medicaid-compliant tools when appropriate). NY Wills & Estates offers appointments in Manhattan (450 7th Avenue) and Hackensack (15 Warren Street).